Recently a bioarchaeological paper on a Southeast Asian sample that I was an author was rejected by an international biological anthropology journal. Although the reviewers deemed the paper to be scientifically sound the Academic Editor rejected it based on a subjective value judgement that the results weren’t “significant or new” and recommended that it would have been “more suitable for a regional journal”. I couldn’t help but think that if it was something from other parts of the Old World that it would have been published, and that the work we are doing in Southeast Asia is not seen as important, despite addressing issues of direct relevance to the international archaeological research community. Our paper was significant in extending knowledge on the nature of agricultural development and human stress response in a tropical rice based environment, which challenges the universally applied model of health change. Never mind that half the world’s population lives in rice subsistence based societies, nor what our work can inform on the epidemiology of disease in tropical environments, and the unique archaeological context of socio-political and agricultural development that our research can address.

So to turn this negative energy into something constructive, I thought that I would showcase some recent Southeast Asian bioarchaeological work that was presented at a panel that Marc Oxenham (Australian National University) and I organised at the recent Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization Regional Centre for Archaeology and Fine Arts (SEAMEO SPAFA) conference this week. The papers comprise some of the enlarging corpus of bioarchaeological work that is being done by local SE Asians and foreign researchers in the region (see also the recently edited volume The Routledge Handbook of Bioarchaeology in Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands). Recent bioarchaeological research in Southeast Asia has been instrumental for illustrating variance to the internationally applied models of population biological response to agricultural development and intensification. There has been an increased interest in the bioarchaeological testing of explanatory models of the occupation of Mainland Southeast Asia, including a debate surrounding the suitability of the two-layered (replacement) settlement model, also of relevance to models of settlement in other parts of the world. Our session included papers with a range of methodological approaches including funerary analyses, dental and skeletal palaeopathology, isotopic analyses of diet and migration, and physical activity through entheseal (muscle attachment) changes.

The session commenced with work addressing broad issues of subsistence and natural and social environmental changes, and migration in the region. Marc Oxenham (co-authored with Anna Willis) started the session by interrogating what the ‘Neolithic’ in Southeast Asia means and asks the question of what influence farming in the region had on these communities and what implications this has for bioarchaeological interpretations. If populations are already sedentary and have high fertility and large settlement sizes, then would a pre- versus post-agricultural palaeopathological comparison be appropriate? I have also previously touched upon the issue of classification of sites into these categories here.

Charlotte King (University of Otago) then turned to a site-specific example of testing human variation during the agricultural transition using isotopic analyses to indicate diet and migration and geometric morphometrics as a genetic proxy from the prehistoric Thai site of Ban Non Wat. She did not find any definitive evidence for population replacement of the hunter-gatherer population by the early agriculturalists.

I presented a new biosocial model that is dovetailing the raft of archaeological and bioarchaeological evidence for a rapid socio-political and biological (‘health’) change in the Iron Age in the Upper Mun River Valley in northeast Thailand. By assessing the bioarchaeological evidence within an epidemiological context of the changing natural and social environment, we are starting to understand the changes of mortality and morbidity through transmission modes and the possible aetiologies of disease during this time.

In light of the model of swift change in social organisation and corresponding biological changes that are being seen in the region at this time, Stacey Ward (PhD candidate, Otago) is investigating social organisation and its influence on physiological stress through growth disruption at the Thai Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak.

Rebecca Jones (PhD candidate, Australian National University) then presented on her research that is assessing zooarchaeological evidence for the change in subsistence using two Vietnamese archaeological assemblages, the pre-agricultural site of Con Co Ngua, and the agricultural site of Man Bac, Vietnam.

Korakot Boonlop (PhD candidate, Leicester) presented preliminary oral pathology data from the Neolithic site of Nong Ratchawat in West-central Thailand. Comparative analyses from other sites in the region from later periods will provide a means to assess the impact of oral health with the intensification of agriculture.

Several papers addressed issues of cultural processes on the living and the dead. Rebecca Crozier (University of the Philippines) presented some fascinating evidence for cranial modification from Cebu in the Philippines. This research is starting to look not only at the cultural aspects of this practice, but also the health implications that this modification can have on individuals.

Melandri Vlok (Honours graduate student, ANU) presented a contextualised interpretation of the bioarchaeology of care of an individual who had sustained major leg trauma at the Metal period site of Napa in the Philippines. This lead to some interesting discussions poolside after the session for the development of the bioarchaeology of care model being applied to infants and children in past societies.

Myra Lara (Graduate student, University of Philippines) showcased the diversity of archaeological mortuary treatment practices in prehistoric northern and central Philippines. Her analyses attempted to correlate mortuary treatment over time and space within the Philippines and other Islands within the wider region.

Two talks looked at evidence for activity in the past and interpreted them with wider archaeological and other contextual evidence. Dicky Caesario Wibowo (Masters student, University of Indonesia) presented his analyses of physical activity based on entheseal changes from the late prehistoric site of Gilimanuk, Bali.

Sarah Agatha Villaluz (Graduate student, University of Philippines) assessed activity using entheseal changes in a sample from 18th century burial sites from the Philippines, and used historical and ethnographic evidence in her interpretation of possible habitual activities.

Other sessions at the conference also had biological anthropology papers, including a session on Ifugao archaeology and one on Palaeolithic archaeology.

Unfortunately a number of researchers not mentioned above couldn’t make it to our session because of the cost, which was especially prohibitive for Southeast Asian scholars. However, despite this, our session was one of the biggest at the conference, indicating the increased development of local expertise in the area. This success has stimulated me to start organising the next Southeast Asian Bioarchaeological Conference that we hope will be held in 2017. The last meeting was held in 2012 in Khon Kaen in Northeast Thailand and supported the attendance of over 70 delegates from 11 different countries. The main aim of these conferences are for the training and professional development of local students and academics in the field of bioarchaeology.

Photos courtesy SEAMEO-SPAFA

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1.

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1. A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand.

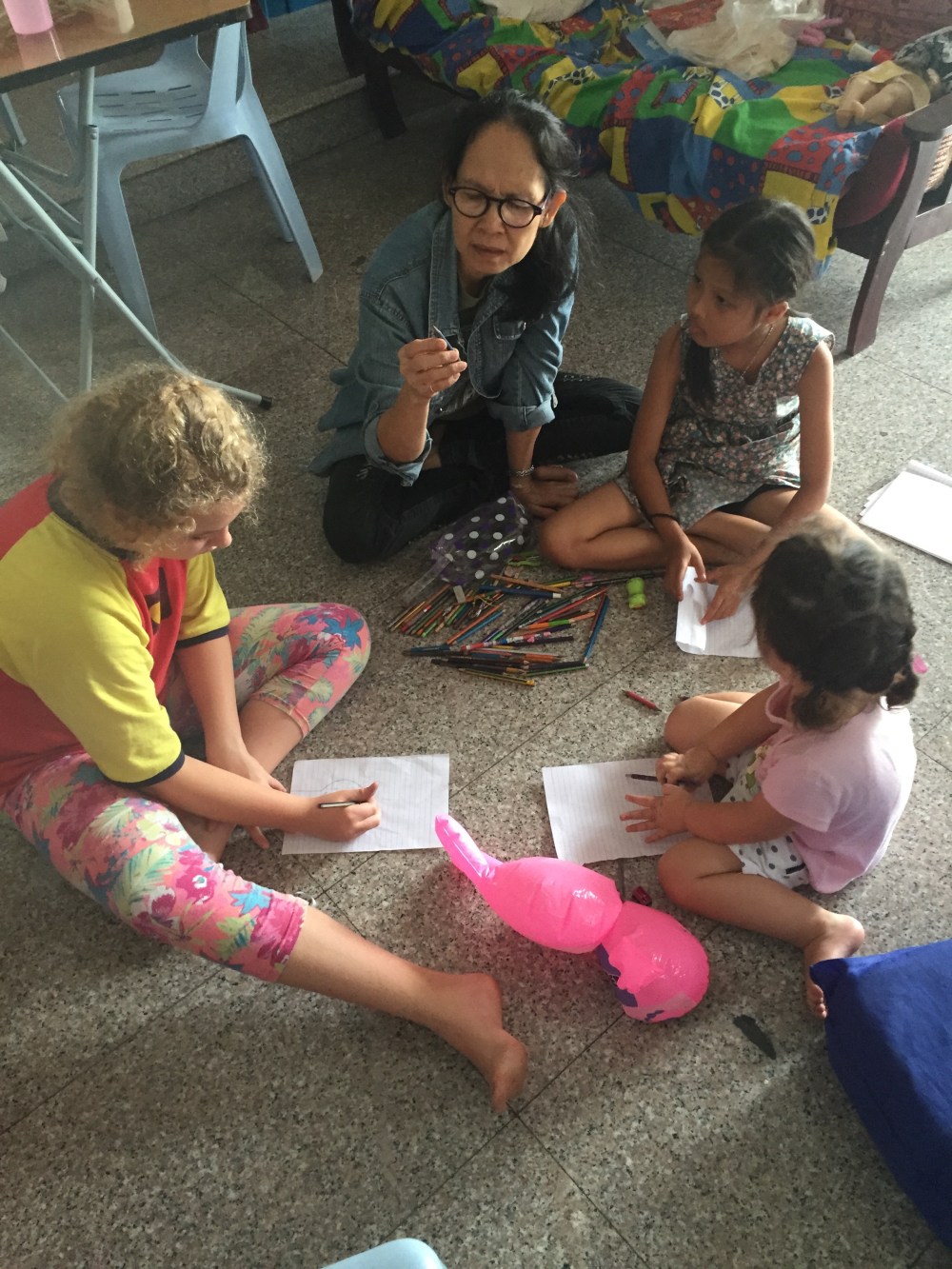

A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand. Our “super-nanny”.

Our “super-nanny”. The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains.

The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains. The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.

The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.