Alien from the Atacama: What baby osteology can tell you

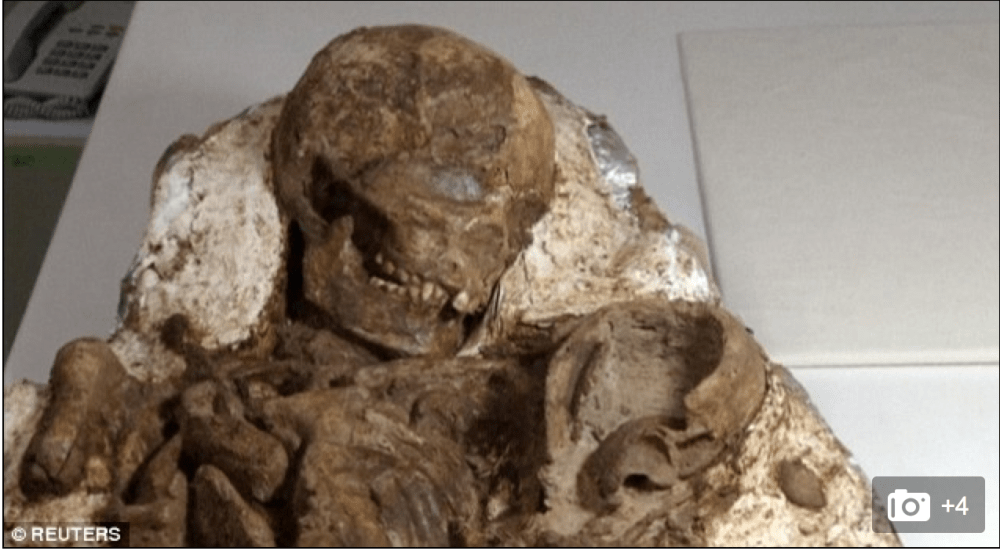

Numerous alien and conspiracy theories have been put forward in the past to explain archaeological finds. One such example that has gained significant media attention is the partially mummified human fetus given the name “Ata” after being found in the Atacama Desert in Northern Chile in 2003. The alien theories and human growth disorder theories that have been put forward are based on the purported unusual skeletal and soft tissue morphology. In 2013, it was reported by geneticist Garry Nolan that the DNA analyses supports that the individual is human. However at this same time it was reported that Ralph Lachman (clinical pediatric radiologist) claimed the skeletal biology was not human-like, citing numerous observations, including “the high level of calcification observed in the legs suggested it was more likely a child between the ages of five and eight years old”.

Figure 1: Naturally mummified fetus from the Atacama Desert, Northern Chile.

Recently I was approached by a researcher, let’s call him Mr X, who was producing a report from his re-examination of the Atacama specimen. When Mr X asked my opinion to be used in his report he didn’t supply me with any primary data to base my analyses on, so my preliminary observations were based on photos I could find online. Prior to my correspondence with Mr X my colleague based in the UK was asked to comment on the specimen from an ancient DNA perspective. Although the draft report that Mr X emailed for my comments after I had given my preliminary observations concludes that this individual is most likely a human fetus, which I agree with, I was dismayed with a number of things.

Firstly, in this report draft, my colleague’s comments were taken out of context and severely criticized, and included in the report without consent. Perhaps this was because my colleague declined to be sucked into spending precious time and several thousand pounds (things that are not plentiful for scientists these days!) on aDNA analyses of the individual. I should note that my colleague was not worried about Mr X’s criticism of him, but it raised alarm bells for me.

The second issue, and one that I want to discuss here is the lack of proper osteological analyses and reporting, which reminded me somewhat of Dr Kristina Killgrove’s Who Needs an Osteologist installments. Mr X asked me to comment on Mr Z’s (human anatomist and embryologist) interpretations of his findings before writing the report. Mr X advised me to keep the report confidential, as this was being prepared for the private ‘owner’ of the remains based in Spain. The ownership of archaeological remains is problematic in itself. While Mr X had perfectly valid interpretations, a human osteologist’s input is needed for valid scientific analyses of human bone, methodological description and interpretations of the findings. I saw no explanation of age estimation methods, no reference to any human osteological developmental texts, and no inclusion of any studies of mummified soft tissues. As well as bad reporting, Mr X did not acknowledge my input into his findings.

Although I am not going to release the contents of the report, I want to share with you some of my communications with Mr X. Here are some of my explanations of previous biological ‘anomalies’ argued to exist in the Atacama specimen.

1st ‘anomaly’: The 11th and 12th pair of ribs seem to be missing in the radiographs.

My response: The ribs may not be visible in a radiograph as the 11th and 12th ribs are smaller ‘floating’ ribs in that they do not articulate anteriorly at the sternum, are not as robust, and are shorter that the other ribs. There is little information about the formation of ribs in-utero and the timing of the primary centres of ossification (where they first start forming as bone). Initial formation of the 5th-8th ribs start at about 8th-9th weeks in-utero (Scheuer and Black 2000: 238). Scheuer and Black (2000: 238) also state that “by the eleventh and twelfth weeks of intra-uterine life, each rib (often with the exception of the twelfth)”, which implies that the lower ribs are later forming, so may not be as visible in a radiograph.

2nd ‘anomaly’: The seemingly advanced stage of epyphiseal union of the femur, suggesting an age of 5-10 years.

[epiphyseal fusion refers to when the shaft of the bone and the extremity fuse together when the bone stops growing in length]

My response: The statement of the advance stage of epiphyseal fusion is incorrect. If there was fusion/union at the distal femur (which I am assuming they are talking about) this would suggest an adolescent, and thus older than 5-10 years. Regardless of this error in age estimation from epiphyseal fusion methods, I do not see evidence for union on the radiograph online – where is the ‘density’ that they are referring to? There is no ossification of the epiphyses (the unfused extremities of the femora or tibiae) to suggest that fusion of the diaphyses (shaft) and the epiphyses (extremity) would be possible. These bones and the development of these bones all look normal from my observations of the photos and radiographs online.

3rd ‘anomaly’: The epiphyseal plate x-ray density test for age determination suggested an age of 6-8 years old.

My response: This type of age estimation is problematic, and I don’t know any bioarchaeologist or forensic anthropologist who uses the method described. This can’t be applied to mummified remains if it relies on water density.

This is no alien. This was the result of a mother losing her baby early during her pregnancy in the past in South America.

Figure 2: My archaeologist colleague on our trip to an archaeological site in Arica region, Atacama desert, Chile.

Also see my post on human fetuses in the past here.

Figure 1: The 4800-year-old “mother and baby” found in Taiwan (source: Reuters)

Figure 1: The 4800-year-old “mother and baby” found in Taiwan (source: Reuters) Figure 2: Archaeologist cleaning the ‘mother-baby’ burial (photo: Reuters video).

Figure 2: Archaeologist cleaning the ‘mother-baby’ burial (photo: Reuters video).

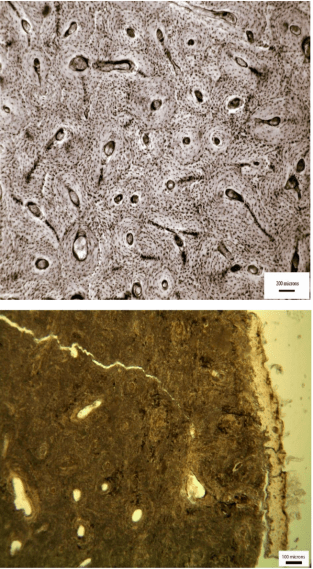

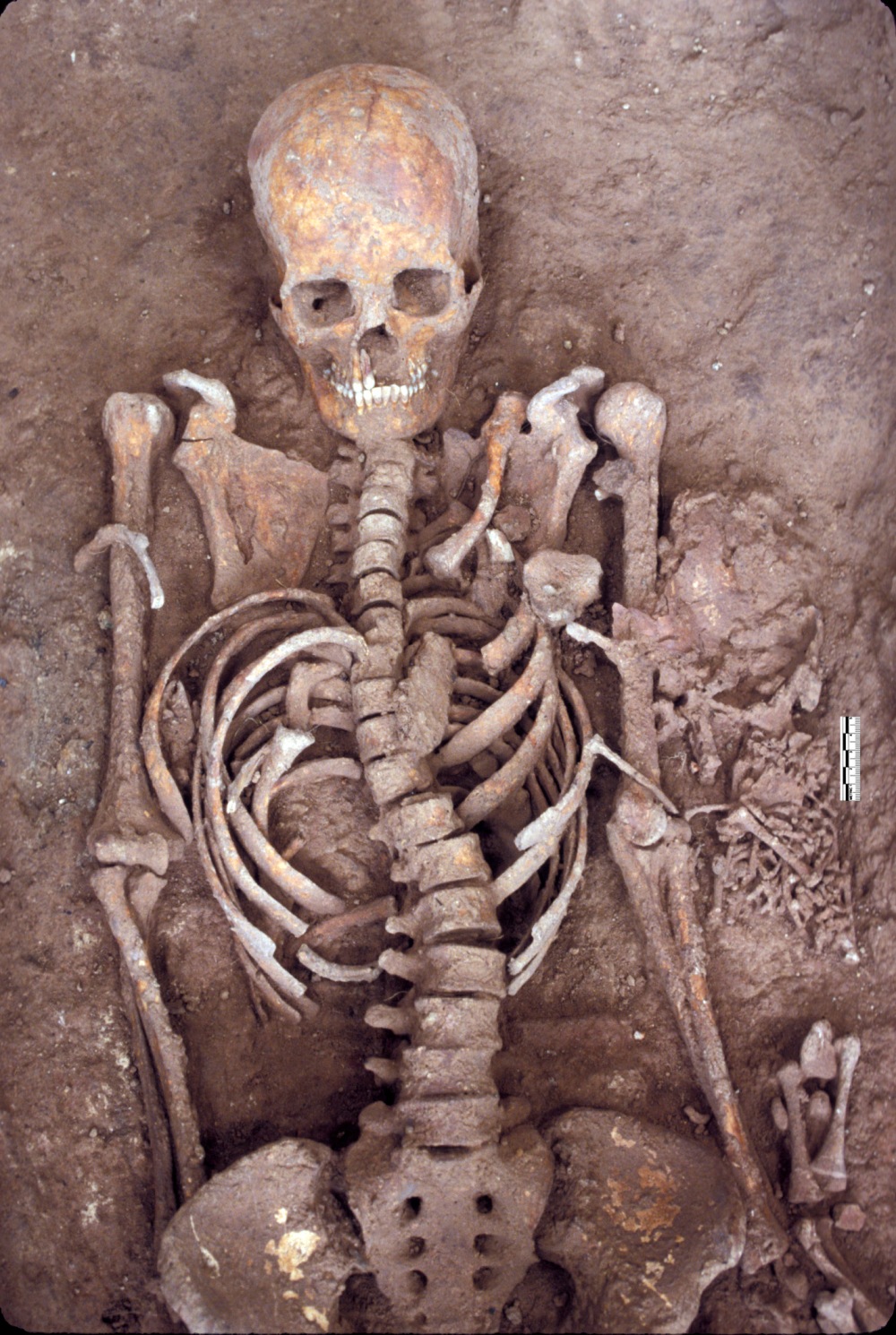

Probable mother and newborn death from the ‘Neolithic’ site of Khok Phanom Di, Southeast Thailand. This site had a infant death representation of over 40% of the cemetery sample.

Probable mother and newborn death from the ‘Neolithic’ site of Khok Phanom Di, Southeast Thailand. This site had a infant death representation of over 40% of the cemetery sample. A ‘foetal’ (preterm) birth from the site of Ban Non Wat, Bronze Age, Northeast Thailand. If a live birth, this baby wouldn’t have lived for long after birth because of its immaturity.

A ‘foetal’ (preterm) birth from the site of Ban Non Wat, Bronze Age, Northeast Thailand. If a live birth, this baby wouldn’t have lived for long after birth because of its immaturity.