Forgotten histories: what fetal and baby remains in medical collections tell us about inequality

Read coverage of our new research here in The Conversation.

Read coverage of our new research here in The Conversation.

A reminder that the 13th Annual SSCIP Conference is being held via Zoom from the 25th to 28th of October (British Summer Time). It is hosted and organised by Associate Professor Siân Halcrow of the University of Otago, New Zealand, and has been scheduled into eight short sessions over four days to accommodate the different time zones of participants.

Keynote addresses will be made by Professor Maureen Carroll of the University of York, Associate Professor Alison Behie of Australian National University, Professor Holly Dunsworth of the University of Rhode Island, and Professor Sarah Knott of Indiana University Bloomington.

If you are interested in attending any of the eight sessions you can register for free using the following link: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/society-for-the-study-of-childhood-in-the-past-conference-tickets-179748280947. After you register you will be sent a confirmation email. Zoom details for the event can be found by clicking the “View the event” button in this email.

Information regarding the conference schedule and abstracts for all the talks can be found at the following link: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1TqiAhXRo9NEiHPqTD1_OxOgh-wxf4dt0_jcIHQaWG2Y/edit?usp=sharing

Session times:

Day One / 25th October 2021 – Session One: 8am – 10am BST

Day One / 25th October 2021 – Session Two: 9pm – 10pm BST

Day Two / 26th October 2021 – Session One: 8am – 10am BST

Day Two / 26th October 2021 – Session Two: 9pm – 10pm BST

Day Three / 27th October 2021 – Session One: 8am – 10am BST

Day Three / 27th October 2021 – Session Two: 9pm – 11pm BST

Day Four / 28th October 2021, Session One: 8am – 10am BST

Day Four / 28th October 2021 – Session Two: 9pm – 11pm BST

The collection of papers in this special issue of Childhood in the Past edited by Francesca Fulminante showcase research on infancy and childhood with sophisticated theoretical and methodological approaches to this topic. This issue represents a significant contribution to understanding the role of children and childhood during the transition to urbanization in Europe through the lens of multiple approaches, including bioarchaeological, archaeological, cognitive developmental (palaeoanthropological), sociological and historical research on infants and children, using a variety of new analytical techniques. This issue moves chronologically from the consideration of cognitive development during prehistory to the nineteenth-century urban environment. Check it out!

Personal Reflections By Amanda Hoogestraat, Twitter @AmehAnthro

On my recent tour of museums in the UK, I saw small reminders of children in the exhibits featuring past societies. Children were obviously a part of every community, but are underrepresented in museum collections. There is a museum devoted to childhood in both London and Edinburgh, but perhaps other museums should consider adding more children’s items to their collections for a more balanced representation of life in the communities it displays.

For many of the museums that had childhood material culture, shoes or cradles were the only items on view.

Four out of the 55 museums that I visited had children’s skeletal remains on display; usually infants and mostly with an adult skeletons nearby. Rarely did I see older children.

However, it was the toys that interested me the most; to see how the cherished play items were very similar to those of today.

I also observed how visiting children interacted with the exhibits, especially at museums not designed specifically for them. Some of these museums had created play areas pertaining to a display nearby.

Surprisingly, the British Motor Museum was a place that had children’s programs and school tours.

I think everyone enjoys seeing items from a childhood different from our own lives or from our own childhoods. It reminds us that across time and location, children were an integral part of the society.

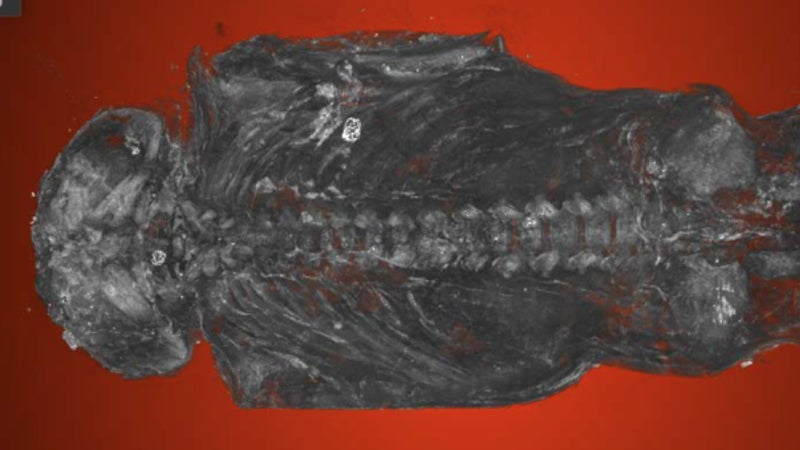

Recently researchers have made an unexpected discovery of a mummified foetus while CT scanning a 2300-year-old mummy known as Ta-Kush currently held at the Maidstone Museum in Kent. This coffin was labelled, “A mummified hawk with linen and cartonnage, Ptolemaic period (323 BC – 30 BC).”

Micro-CT scan shows the mummified stillborn human baby. Image: Maidstone Museum UK/Nikon Metrology UK

Micro-CT scan shows the mummified stillborn human baby. Image: Maidstone Museum UK/Nikon Metrology UK

The high resolution CT scan results have recently been presented at the Extraordinary World Congress on Mummy Studies in the Canary Islands last month. The authors argue that the foetus was about 23-28 weeks gestation and had anencephaly as shown by underdeveloped skull bones.

To me, this begs the question as to whether the several other Egyptian ‘hawk’ mummies curated around the world are actually tiny babies. Further investigation of this baby and others will shed light on the social responses of grief and loss of those born too young to survive.

Watch here on YouTube Mummy ‘bird’ mystery

The intricate relationship between mother and infant health is becoming more acknowledged in archaeology, with the increase in reporting and publication of cases of maternal and foetal death. The fantastic Kristina Killgrove has recently written a story on a rare case on coffin-birth from Mediaeval Italy. Check it our here!

The Atacama Desert is well-known for the earliest evidence in the world for deliberate mummification of the dead, predating Egyptian mummies by more than two millennia. The intricate funerary rituals associated with the pre-agricultural Chinchorro people of this area were largely focused on infants and children. This has led some to hypothesise that it was a social response to high rates of foetal, infant and maternal death in these populations. Historically, archaeological research in the Atacama has focused on these pre-agricultural mummies, but recent research has highlighted periods of increasing infant mortality later in prehistory – during the transition to agriculture. The ultimate causes of this increase in stress, however, have eluded archaeologists.

The project took a two-pronged approach to this problem, studying changes to diet using chemical signatures in bones and teeth, and assessing their health impacts by looking for signs of pathology on the skeletons of early agricultural populations. Published recently in the International Journal of Paleopathology, and covered here, an Early Formative Period site just transitioning to agriculture (3,600-3,200 years before present) showed that all the infants have evidence of scurvy (nutritional vitamin C deficiency). Interestingly, so did an adult female found buried with her probable unborn child. First author Anne Marie Snoddy says “In addition to contributing to knowledge of the interplay between environment, diet, and health in the Ancient Atacama, this paper provides the first direct evidence of potential maternal-foetal transference of a nutritional deficiency in an archaeological sample”.

This study also used new methods for analysing diet and stress using the chemistry of bones and teeth, these also reveal a picture of early-life stress recently published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology and covered by Forbes. “The preservation of mummies in the Atacama gives us an unprecedented opportunity to use tooth chemistry to look at prehistoric infant experience. We have chemical evidence of stress from tissues which form even before the infant is born, showing how the mother’s health is impacting her baby” says author Charlotte King. This work contributes to an understanding of the sensitive relationship between the health of the mother and infant in the past, including the maternal-infant transference of stress signals and micronutrient deficiencies.

Anne Marie Snoddy doing her palaeopathological analyses in the Museo Universidad de Tarapacá San Miguel de Azapa, Arica, Chile.

The research is giving new insight into human adaptation to one of the harshest environments in the world. The Atacama Desert experiences less than 2 mm per year of rainfall, making agricultural resources very vulnerable. However, the marine environment is remarkably rich, owing to the upwelling of the cold Humboldt ocean current, resulting in an abundance of marine mammals and fish. Chemical analysis is showing that the people of the desert buffered themselves against the vulnerability of their agricultural resources by continued reliance on these marine foods. Even so, periodic food shortages from El-Niño events in the area were likely, and the skeletal evidence for vitamin C deficiency is interpreted as being related to these events.

A version of this story was originally published here.

This month we are featuring Dr Tracy Betsinger who is an Associate Professor from SUNY Oneonta. Prior to joining SUNY Oneonta, Dr. Betsinger held a post-doctoral research position with the Global History of Health Project at Ohio State University.

Tracy working on a perinate from the post-medieval Drawsko collection, Poland (while pregnant with a fetal skeleton shirt on!).

Tell me a little bit about your work:

I’m a bioarchaeologist interested in patterns of health (in general) and infectious disease, particularly treponemal disease, the effects of cultural factors such as status and urbanization on health, and the relationship between mortuary patterning/treatment and identity/personhood, especially among perinates. I work on materials from a variety of contexts, including prehistoric populations from eastern Tennessee and medieval and post-medieval populations from Poland.

How did you get into your field and why?

My interest in perinatal mortuary patterning was a fortuitous happenstance. While working with a colleague, Dr. Amy Scott, on post-medieval Polish materials, we noted the fairly large number of perinatal remains, many of which were well preserved (several with the tympanic rings in place!). We were examining other mortuary patterns at the time, when we decided to investigate the perinatal mortuary pattern to determine whether it matched older subadults or was distinct in some way. We also explored what this might mean in terms of their personhood and identity. The more I began to research perinates, perinatal mortuary patterns, and ontology, the more intrigued I became. I shared my research with a cultural anthropologist in my department (Dr. Sallie Han) whose research is focused on pregnancy and we found much common ground! The result of this was a four-fields anthropology of fetuses, initially an American Anthropological Association session and now a soon-to-be in-press edited volume.

What is on the future horizon for your research?

More recently, I have begun exploring perinatal mortuary treatment with the prehistoric populations from Tennessee. This work is just beginning, but I’m hoping to explore perinatal mortuary patterns/personhood temporally and geographically in the region and dovetail that information about what we know is going on health-wise in East Tennessee. My colleagues (Dr. Michaelyn Harle, Dr. Maria O. Smith) and I have only completed some general assessments of perinates, but so far, there seems to be a consistency in their treatment with older subadults and across time and space. We are planning more nuanced analyses of their mortuary treatment and are hoping to analyze remains for bacterial bioerosion with the hopes of identifying stillbirths from live births.

We have a forthcoming large annotated bibliography on the Bioarchaeology of Childhood coming soon to Oxford Bibliographies online. Take a sneak peek here. This will be useful to all bioarchaeology and human osteoarchaeology students, and academics for research and teaching. Please contact me here to request a personal copy.

Note that this is now published online

Halcrow, Siân E.; Ward, Stacey M. “Bioarchaeology of Childhood.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Childhood Studies. Ed. Heather Montgomery. New York: Oxford University Press, forthcoming.

Recently, there has been a study published by researchers at my own University on the experience of Research and Study Leave (RSL) or sabbatical for men and women. It found that families are negatively affected to taking RSL with international travel due to childcare requirements and associated costs.

I am lucky that I am in a permanent position and at a University that supports RSL. I am also ‘lucky’ that I have recently sold my house. The small proceeds from this have allowed me to pay for my 2- and 11-year-olds airfares and childcare, which has thus far cost over NZ$15,000, plus continued payment of daycare fees to keep the enrollment of my 2-year-old at our University childcare.

What I am truly lucky for is the child-centered cultures that I work in and the amazing colleagues and students I have who accommodate them. The best place in accommodating my children has been in Thailand and Laos where friends and my local nanny have been absolutely fabulous. I have tried to plan this stint of fieldwork so as my 11-year-old is away at a time that includes her school break and to work around a visiting fellowship to the UK at the end of the year. However, this timing has also meant that it is HOT and hard for my kids. My 11-year-old misses her friends, but she has been extraordinarily self-motivated at doing her schoolwork each day (even in the weekends) working on her maths, reading and writing. I actually have to tell her to stop doing it at times so she gets out of the house!

Research highlights thus far have been working on the human remains from the Plain of Jars site in Laos excavated under the direction of Dougald O’Reilly and Louise Shewan. This site is under consideration for World Heritage Status and has gained archaeological interest from researchers around the world. I have also been continuing with my data collection from the infants and children from a Thai Iron Age site (see my post from early this year). This season I have found several very pre-term infants. This is of significance in indicating poor maternal health in this past population, and further supports our developing model of health change during this turbulent time of agricultural and social change.

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1.

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1.

A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand.

A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand.

Our “super-nanny”.

Our “super-nanny”.

The most difficult place we have been this year for accommodating children was the US for two major conferences. Childcare was US$200 a day plus extra expenses. Neither of the conferences provided childcare services, which I would have been very happy to pay for. Thank goodness for two local moms at the first conference who traveled to the store to buy us some groceries while we were stuck in a food desert! Despite the expense, both conferences have been extremely beneficial for my research. I have established new collaborations, been invited to visit universities, and they were invaluable for me to keep up-to-date with recent research developments in my field. I was also able to support two of my students who attended the conferences.

I’m happy that my RSL so far has been possible with my children. Without the ability for international travel I can’t do my research or attend major conferences. However, next time I will try to be more realistic about my plans with the kids. They are enjoying their time in Southeast Asia but the logistics and financial issues are a lot of pressure.

We are off to the UK in September until December for my fellowship to work with colleagues in the Department of Archaeology at the University of Durham. Another place with supportive colleagues! I’m looking forward to the next adventure!

The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains.

The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains.

The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.

The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.