The concept of fetuses in archeology probably brings to mind poignant images of the tiny bones of a baby in the pelvic cavity of a female adult skeleton, although finds such as these are actually rather rare. In practice, many bioarchaeologists apply the description of ‘fetus’ to babies from bioarchaeological samples identified as younger than 37 weeks gestational age (e.g. Halcrow et al. 2008; Lewis and Gowland 2007; Mays 2003; Owsley and Jantz 1985). However, there are problems associated with estimation of age-at-death of these babies, who may indeed be fetuses, but also may be premature births, or small-for-gestational age full-term births. If the medical definition of a fetus as an unborn baby is applied (Forfar et al. 2003; Halcrow and Tayles 2008; Lewis and Gowland 2007; Scheuer and Black 2000), the in-utero skeletons would seem to represent the only finds in archaeology that can be confidently identified as fetuses. However, even an apparent in-utero fetus may in fact have been a neonate mortality, illustrating the care with which research in this field needs to be completed.

Generally little bioarchaeological research considers fetuses. For example, some growth studies and demographic analyses do not include preterm infants because of lack of comparative fetal bone size data (e.g. Johnston 1961). Also, the attention afforded to purported evidence of infanticide, based primarily on the reported high number of perinates in some skeletal assemblages (see my previous blog story on this), has deflected interest away from the contributions that fetuses can make to understanding bioarchaeological questions, including maternal health and disease and social organization from mortuary ritual analyses (Bonsall 2013; Faerman et al. 1998; Gilmore and Halcrow 2014; Mays and Eyers 2011; Mays 1993; Mays and Faerman 2001; Smith and Kahila 1992).

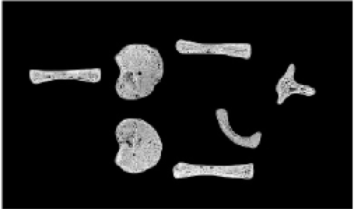

It is believed that approximately 3 in 10 pregnancies are spontaneously aborted, with the majority of these occurring in the first trimester, most being the result of genetic abnormalities (Fisher 1951). First trimester fetuses are very unlikely to be recovered in the bioarchaeological context. Bone development does not start until approximately six–eight weeks gestational age, and any bone formation prior to the second trimester would be unlikely to be preserved because of the low level of mineralization, and/or would be extremely difficult to identify in an archaeological context. The only first trimester fetus reported from an archaeological context is from the Libben sample, Ohio, a Late Woodlands site occupied 8th-11th century AD (White 2000: 20, see figure 1). There are published instances of preserved fetal individuals from the second trimester, e.g. the well-preserved fetus of 20 weeks gestational age from the Kellis 2 site, Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt (Wheeler 2012: 223). Owsley and Jantz (1985) have found three fetuses younger than 28 weeks gestation at Arikara sites in South Dakota. Hillson (2009) has also reported the findings of fetuses as young as 24 gestational weeks from a large Classical period infant cemetery at Kylindra on Astypalaia, in Greece.

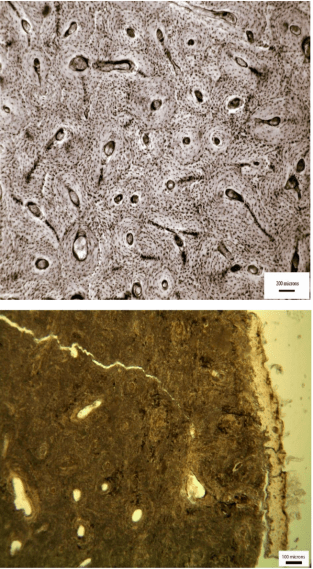

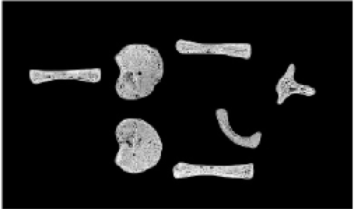

Figure 1. Fetal skeletal material from the prehistoric Libben site, the smallest burial ever recorded (from White et al. 2011: 329). The long bones measure less than 2 cms.

Types of fetus burials

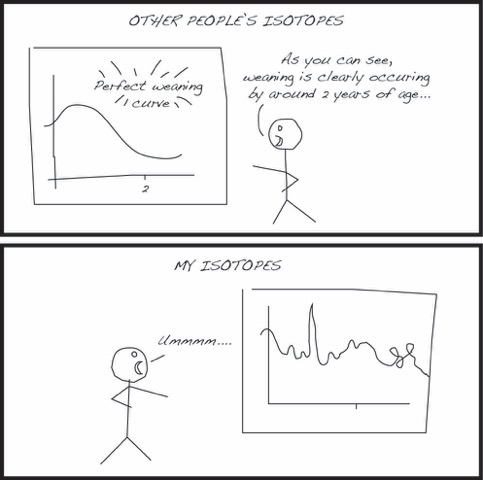

Differentiating burial types has the potential to contribute to research on maternal health, and the cause of death for the mother and child in the past. For example, a premature birth is more likely to indicate poor health and/or nutritional status of a woman, compared with a baby who died around full-term from obstructed labor. Distinguishing the type of fetal death and burial, whether the baby was full-term, or a pre-term or small-for gestational age baby, in conjunction with evidence of stress and diet and of both the mother and baby may give insights into overall health in past populations (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Infant jar burials from the Iron Age site of Noen U-Loke, NE Thailand. Left: full-term infant, approximately 40 gestational weeks (burial 100); right: pre-term infant, or ‘fetus’, approximately 30 gestational weeks (burial 89). (Photograph courtesy of C.F.W. Higham)

Figure 2. Infant jar burials from the Iron Age site of Noen U-Loke, NE Thailand. Left: full-term infant, approximately 40 gestational weeks (burial 100); right: pre-term infant, or ‘fetus’, approximately 30 gestational weeks (burial 89). (Photograph courtesy of C.F.W. Higham)

In-utero fetuses

If the skeletal remains of a baby are found crouched in a fetal position within the pelvic cavity of an adult female, the mother likely died while the fetus was in-utero, before or during labor. The pregnant woman may therefore have died due to pregnancy or labor complications (Lewis 2007: 34). There is very little evidence for in-utero fetuses in the bioarchaeological context. Approximately 20 cases of pregnant or laboring females (i.e., interred with fetal remains in-situ) have been published in the archaeological literature, being argued to represent complications from childbirth (e.g. Ashworth et al. 1976; Cruz and Codinha 2010; Hawkes and Wells 1975; Högberg et al. 1987; Smith and Wood-Jones 1910, in Lewis 2007; Lieverse et al. 2015; Malgosa et al. 2004; O’Donovan and Geber 2010; Owsley and Bradtmiller 1983; Persson and Persson 1984; Pounder et al. 1983; Rascon Perez et al. 2007; Sjovold et al. 1974; Roberts and Cox 2003; Wells 1978).

The dearth of literature on in-utero fetuses in bioarchaeology may not be due to absence of evidence, but rather from the small bones being missed or misidentified during excavation, or reported only in the grey literature. There are numerous accounts of fetuses being misidentified as animal bones during excavation (e.g. Ingvarsson-Sundström 2003). For example, Roberts and Cox (2003) have reported at least 24 unpublished cases of fetuses from British excavations. There are further instances of fetal bones being found co-mingled with adult burials post-excavation, which may represent a baby in-utero, or a possible mother and baby post-birth burial (S. Clough, pers. comm.).

Bioarchaeologists have reported on cases of purported obstructed labor causing maternal and fetal perinatal death based on positioning of the fetus in the pelvic cavity or the finding of preterm mummified remains in-utero (Arriaza et al. 1988; Ashworth et al. 1976; Lieverse et al. 2015; Luibel 1981; Malgosa et al. 2004; Wells 1975).

Post-birth ‘fetuses’

If a perinate is found buried alongside an adult, with the same head orientation, then the infant has been buried post-birth, whether naturally or by caesarian section (Lewis 2007: 34) (Figure 3). In some contexts it is very common for newborns to be placed on the chest of adult women (presumably their mother) (Standen et al. 2014). To identify post-birth ‘fetuses’ archaeologically, if the majority of the infant remains are in the pelvic cavity of the adult, yet the legs are extended and/or the cranium lies among the ribcage, then the baby may have been delivered and then placed on top of the mother’s (or other adult’s) torso during burial (Lewis 2007: 34). It is argued that as both mother and baby bodies’ skeletonize, the baby’s bones can become settled among the mother’s ribs and vertebrae. This is important to note as these neonates may be mistaken for breech, obstructed labors in the archaeological context (e.g. Willis and Oxenham 2013). Willis and Oxenham (2013) describe an ‘in-utero breech’ presentation of a 38 gestational week fetus from Neolithic Southern Viet Nam. They describe the cranium as “below the mother’s right lower ribs” (it is not clear if they mean inside the abdominal/thoracic cavity or inferior to the right lower ribs) and the postcranial skeleton as “extended down toward the mother’s pelvis” with the left femur “positioned within the mother’s pelvic cavity and a tibia … positioned beside [lateral] the lesser trochanter of the mother’s right femur.” They also state the “right pars lateralis [part of the base of the occipital bone of the cranium] was concreted to the anterosuperior portion of the shaft of the 10th right rib of the mother, near the sternal end.” Given this partially extended (non-fetal) positioning and the part of the cranial base being found anterior to the rib cage), it could be possible that the baby was not in the abdominal cavity, but placed on top of the mother’s torso after birth.

Figure 3. Full-term neonate (burial 48) buried alongside an adult female (burial 47) from Khok Phanom Di (photograph courtesy of C.F.W. Higham). This could possibly represent a perinate and mother who died from complications during or following childbirth.

Ancient DNA analyses may be used to assess the relationship of the adult and fetal burials where the fetus has been placed on the purported mother, or the archaeological context is unclear. Lewis (2007: 35) has argued that this is important to distinguish these relationships, as in some contexts, e.g. in the Anglican burial tradition, babies were interred with non-maternal women in instances of coinciding death (Roberts and Cox 2003: 253).

Multiple fetal pregnancies and births

There have been two reported instances of twin fetuses in-utero in the bioarchaeological literature (Lieverse et al. 2015; Owsley and Bradtmiller 1983), with others found in a post-birth context. There has been a recent increase in the interest in multiple births in bioarchaeology, including an investigation of social identity and concepts of personhood through the investigation of mortuary treatment (e.g. Einwögerer et al. 2006; Halcrow et al. 2012). Human twins are rare, with approximately one occurrence for every 100 births (Ball and Hill 1996). However, they appear in the literature more commonly than expected, compared with singleton fetuses (e.g. Black 1967; Chamberlain 2001; Crespo et al. 2011; Einwögerer et al. 2006; Flohr 2014; Halcrow et al. 2012; Lieverse et al. 2015; Owsley and Bradtmiller 1983). This is probably because they are seen as more significant by the archaeologist.

An example of a possible twin burial was found in an Upper Paleolithic site of Krems-Wachtberg, Austria (Einwögerer et al. 2006). The infants from this double burial were identified as twins from their identical age (as estimated from their dentition), same femora size and their simultaneous interment (both estimated at full-term age at death). Interestingly the bodies lay under a mammoth scapula and a part of a tusk and were associated with 30 ivory beads. Einwögerer et al. (2006) suggest, based on this mortuary evidence, that these newborns were an important part of their community. Another case of a twin burial is from the mid fourth-century site of Olèrdola in Barcelona, Spain (Crespo et al. 2011). The two newborns were found at the same stratigraphic level with their lower limbs entwined, indicating that they were buried simultaneously. We (Halcrow et al. 2012) havev also presented an extremely rare finding of at least two and possibly four twin burials from a 4,000-3,000 year old BP Southeast Thailand site, offering a methodological approach for the identification of archaeological twin (or other multiple birth) burials and a social theoretical framework to interpret these in the past.

Post-mortem birth (‘coffin-birth’)

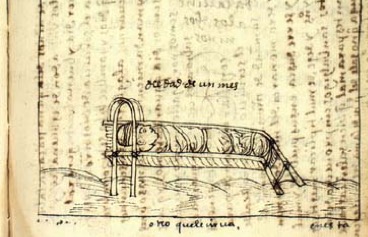

Post-mortem birth or ‘coffin-birth’ refers to the occurrence of fetuses that were in-utero when the mother died and were expelled after burial (O’Donovan and Geber 2010) (Figure 4). This is also talked about by Katy Meyers Emery in her blog story on coffin birth in her blog Bones Don’t Lie. Post-mortem birth by fetal extrusion has been documented in rare forensic cases from the build up of gas within the abdominal cavity resulting in the emission of the fetus (Lasso et al. 2009; Schultz et al. 2005). Lewis (2007: 34-37, 91) and O’Donovan et al. (2009) argue that if fetal remains are complete and in a position inferior to and in-line with the pelvis outlet, with the head oriented in the opposite direction to the mother, then there is the possibility of coffin birth (Figure 3). If they lie within the pelvic outlet, this means that there was partial extrusion during decomposition (Hawkes and Wells 1972). However, partial extrusion could also be the result of an obstructed labor of a baby in the breech position, but this would likely result in extrusion of the lower limbs. Sayer and Dickenson (2015) argue that postmortem fetal extrusion is implausible under some burial conditions and with that decomposition of the baby in-utero would mean that it isn’t likely to be birthed from an undilated cervical canal. This, however, assumes that there was no dilation at the time of death of the mother.

Figure 4. Potential coffin birth (from Appleby et al. 2014)

Social identity

The investigation of mortuary treatment of pregnant women may give us information on social identity related to childbearing and fetuses themselves. For example the discovery of a 34-36 week old fetus cremated with the ca. 850 B.C. “Rich Athenian Lady” led to a recognition that her grave wealth may have been related to her dying while pregnant or during childbirth, rather than primarily her social status (Liston and Papadopoulos 2004).

Research of the archaeology of grief is starting to consider community members’ responses to infant and fetal death (e.g. Cannon and Cook 2015; Murphy 2011). The purported marginalization of fetuses along with infants in the archaeological record, including location and simplified mortuary treatment has led some scholars to interpret that they were of little concern beyond immediate family members (Cannon and Cook 2015). Considering literature on intense grief after miscarriage and infant death starts to challenge the notion that their loss was of little consequence (Murphy 2011).

NB: Part of this story is from the chapter:

Halcrow, S.E., N. Tayles and G.E. Elliott (2016 expected) The Bioarchaeology of Fetuses. In Han S, Betsinger TK, and Scott AB; The Fetus: Biology, Culture, and Society. Berghahn Books. (under contract)

References

Appleby J, Seetah TK, Calaon D, Čaval S, Pluskowski A, Lafleur JF, Janoo A, and Teelock V (2014). ‘The Non-Adult Cohort from Le Morne Cemetery, Mauritius: A Snap Shot of Early Life and Death after Abolition.’ Int J Osteo 24(6): 737-746.

Arriaza B, Allison M, and Gerszten E. 1988. ‘Maternal Mortality in Pre-Columbian Indians of Arica, Chile’. Am J Phys Anthropol 77:35-41.

Ashworth JT, Allison MJ, Gerszten E, and Pezzia A. 1976. ‘The Pubic Scars of Gestation and Parturition in a Group of Pre‐Columbian and Colonial Peruvian Mummies’. Am J Phys Anthropol 45(1):85-89.

Ball HL, and Hill CM. 1996. ‘Reevaluating “Twin Infanticide”‘. Curr Anthropol 37(5):856-863.

Black GA. 1967. Angel Site: An Archaeological, Historical, and Ethnological Study. Indiana Historical Society: Indianapolis.

Bonsall L. 2013. ‘Infanticide in Roman Britain: A Critical Review of the Osteological Evidence’. Childhood in the Past 6(2):73-88.

Cannon A, and Cook K. 2015. ‘Infant Death and the Archaeology of Grief’. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25(2):399-416.

Chamberlain G. 2001. ‘Two Babies That Could Have Changed World History’. Historian 72:6-10.

Crespo L, Subira ME, and Ruiz J. 2011. ‘Twins in Prehistory: The Case from Olerdola (Barcelona, Spain; 2. IV II BC)’. Int J Osteo 21:751-756.

Cruz C, and Codinha S. 2010. ‘Death of Mother and Child Due to Dystocia in 19th Century Portugal’. Int J Osteo 20(4):491-496.

Einwögerer T, Friesinger H, Händel M, Neugebauer-Maresch C, Simon U, and Teschler-Nicola M. 2006. ‘Upper Palaeolithic Infant Burials’. Nature 444(7117):285.

Faerman M, Kahila Bar-Gal G, Filon D, Stager L, Oppenheim A, and Smith P. 1998. ‘Determining the Sex of Infanticide Victims from the Late Roman Era Through Ancient DNA Analysis’. J Archaeol Sci 25:861-865.

Fisher RS. 1951. ‘Criminal Abortion’. J Crim L Criminology & Police Sci 42:242.

Flohr S. 2014. ‘Twin Burials in Prehistory: A Possible Case From the Iron Age of Germany’. Int J Osteo 24:116-122.

Forfar JO, Arneil GC, McIntosh N, Helms PJ, and Smyth RL, editors. 2003. Forfar and Arneil’s Textbook of Pediatrics. 6th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

Gilmore HF, and Halcrow SE. 2014. “Sense or Sensationalism? Approaches to Explaining High Perinatal Mortality in the Past”. In: Thompson JL, editor. Tracing Childhood: Bioarchaeological Investigations of Early Lives in Antiquity. Florida: University of Florida Press. p 123-138.

Halcrow SE, Tayles N, Inglis R, and Higham C. 2012. ‘Newborn Twins from Prehistoric Mainland Southeast Asia: Birth, Death and Personhood’. Antiquity 86:838-852.

Halcrow SE, and Tayles N. 2008. ‘The Bioarchaeological Investigation of Childhood and Social Age: Problems and Prospects’. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 15(2):190-215.

Halcrow SE, Tayles N, and Livingstone V. 2008. ‘Infant Death in Prehistoric Mainland Southeast Asia’. Asian Persp 47:371-404.

Hawkes SC, and Wells C. 1975. ‘Crime and Punishment in an Anglo-Saxon Cemetery?’. Antiquity 49(194):118-122.

Hillson S. 2009. ‘The World’s Largest Infant Cemetery and its Potential For Studying Growth and Development’. Hesperia Supplement:137-154.

Högberg U, Iregren E, Siven C-H, and Diener L. 1987. ‘Maternal Deaths in Medieval Sweden: an Osteological and Life Table Analysis’. Journal of Biosocial Science 19(4):495-503.

Ingvarsson-Sundström A. 2003. Children Lost and Found: A Bioarchaeological Study of the Middle Helladic Children in Asine With a Comparison to Lerna [PhD thesis]. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

Johnston FE. 1961. ‘Sequence of Epiphyseal Union in a Prehistoric Kentucky Population from Indian Knoll’. Hum Biol 33:66-81.

Lasso E, Santos M, Rico A, Pachar JV, and Lucena J. 2009. ‘Expulsión Fetal Postmortem’. Cuadernos de Medicina Forense (in Spanish) 15: 77–81.

—. 2007. The Bioarchaeology of Children: Perspectives from Biological and Forensic Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lewis ME, and Gowland RL. 2007. ‘Brief and precarious lives: Infant Mortality in Contrasting Sites From Medieval and Post-medieval England (AD 850-1859)’. Am J Phys Anthropol 134:117-129.

Lieverse AR, Bazaliiskii VI, and Weber AW. 2015. ‘Death by Twins: A Remarkable Case of Dystocic Childbirth in Early Neolithic Siberia’. Antiquity 89(343):23-38.

Liston MA, and Papadopoulos JK. 2004. ‘The” Rich Athenian Lady” Was Pregnant: The Anthropology of a Geometric Tomb Reconsidered’. Hesperia:7-38.

Luibel AM. 1981. Use of Computer Assisted Tomography in the Study of a Female Mummy from Chihuahua, Mexico. Annual Meeting of the Southwestern Anthropological Associatation. Santa Barbara.

Malgosa A, Alesan A, Safont S, Ballbe M, and Ayala MM. 2004. ‘A Dystocic Childbirth in the Spanish Bronze Age’. Int J Osteo 14(2):98-103.

Mays S. 1993. ‘Infanticide in Roman Britain’. Antiquity 67:883-888.

Mays SA, and Faerman M. 2001. ‘Sex Identification in Some Putative Infanticide Victims from Roman Britain Using Ancient DNA’. J Archaeol Sci 28:555-559.

Mays S, and Eyers J. 2011. ‘Perinatal Infant Death at the Roman VIlla Site at Hambleden, Buckinghamshire, England’. J Archaeol Sci 38(8):1931-1938.

Murphy EM. 2011. “Parenting, Child Loss and the Cilliní of Post-Medieval Ireland”. In: Lally M, and Moore A, editors. (Re)thinking the Little Ancestor: New Perspectives on the Archaeology of Infancy and Childhood BAR International Series 2271. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. p 63-74.

O’Donovan E, Geber J, and Baker C. 2009. ‘Archaeological excavations on Mount Gamble Hill: stories from the first Christians in Swords’. Axes, Warriors and Windmills: Recent archaeological discoveries in North Fingal. Fingal County Council.

O’Donovan E, and Geber J. 2010. “Archaeological Excavations on Mount Gamble Hill, Swords, Co. Dublin”. In: Corlett C, and Potterton M, editors. Death and Burial in Early Medieval Ireland in Light of Recent Excavations. Dublin: Wordwell Ltd. p 64-74227-74238.

Owsley DW, and Bradtmiller B. 1983. ‘Mortality of Pregnant Females in Arikara villages: Osteological Evidence’. Am J Phys Anthropol 74:331-336.

Owsley DW, and Jantz RL. 1985. ‘Long Bone Lengths and Gestational Age Distributions of Post-

Persson O, and Persson E. 1984. Anthropological Report on the Mesolithic Graves from Skateholm, Southern Sweden. I: Excavation Seasons 1980-82. Lund: University of Lund.

Pounder DJ, Prokopec M, and Pretty GL. 1983. ‘A Probable Case of Euthanasia Amongst Prehistoric Aborigines at Roonka, South Australia’. Forensic Science International 23(2-3):99-108.

Rascon Perez J, Cambra-Moo O, and Gonzalez M. 2007. ‘A Multidisciplinary Approach Reveals an Extraordinary Double Inhumation in the Osteoarchaeological Record’. Journal of Taphonomy 5:91-101.

Roberts C, and Cox M. 2003. Health and Disease in Britain: From Prehistory to the Present Day. Thrupp: Sutton Publishing Limited.

Sayer D, and Dickinson SD. 2013. ‘Reconsidering Obstetric Death and Female Fertility in Anglo-Saxon England’ World Archaeol 45(2): 285-297.

Scheuer JL, and Black S. 2000. Developmental Juvenile Osteology. San Diego, California: Academic Press.

Schulz F, Püschel K, and Tsokos, M. 2005. ‘Postmortem fetal extrusion in a case of maternal heroin intoxication.’ Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology 1(4): 273–276.

Sjovold T, Swedborg I, and Diener I. 1974. ‘A Pregnant Woman From the Middle Ages with Exostosis Multiplex’. Ossa 1:3-23.

Smith P, and Kahila G. 1992. ‘Identification of Infanticide in Archaeological Sites: a Case Study From the Late Roman-Early Byzante Periods at Ashkelon, Israel’. J Archaeol Sci 19(6):667-675.

Standen VG, Arriaza BT,and Santoro CM. 2014. “Chinchorro mortuary practices on infants: Northern Chile archaic period (BP 7000–3600)”. In: Thompson JL, Alfonso-Durruty MA, and Crandall JJ, editors. Tracing Childhood: Bioarchaeological Investigations of Early Lives in Antiquity. Florida: University of Florida Press. p 58-74.

Wells C. 1975. ‘Ancient Obstetric Hazards and Female Mortality’. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 51(11):1235.

Wells C. 1978. ‘A Medieval Burial of a Pregnant Woman’. The Practitioner 221:442-444.

Wheeler SM. 2012. ‘Nutritional and Disease Stress of Juveniles from the Dakhleh Oasis, Egypt’. Int J Osteo 22(2):219-234.

White TD, Black MA, Folkens PA. 2011. Human Osteology (Third Edition). Academic Press.

Willis A, and Oxenham MF. 2013. ‘A Case of Maternal and Perinatal Death in Neolithic Southern Vietnam, c. 2100–1050 BCE’. Int J Osteo 23(6):676-684.

Figure 3: A newborn infant from Hambleden site (Credit: BBC)

Figure 3: A newborn infant from Hambleden site (Credit: BBC)

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1.

Our visit to the Plain of Jars site 1. A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand.

A 24-26 week old foetus from the Iron Age site of Non Ban Jak, Northeast Thailand. Our “super-nanny”.

Our “super-nanny”. The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains.

The two-year-old helping me re-box some archeological human remains. The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.

The 11-year-old hiding in our bedroom for some quiet space to do her school work under the mosquito net.

Archaeological child from the ‘Atele site in Tongatapu, Tonga (To-At 2/7)

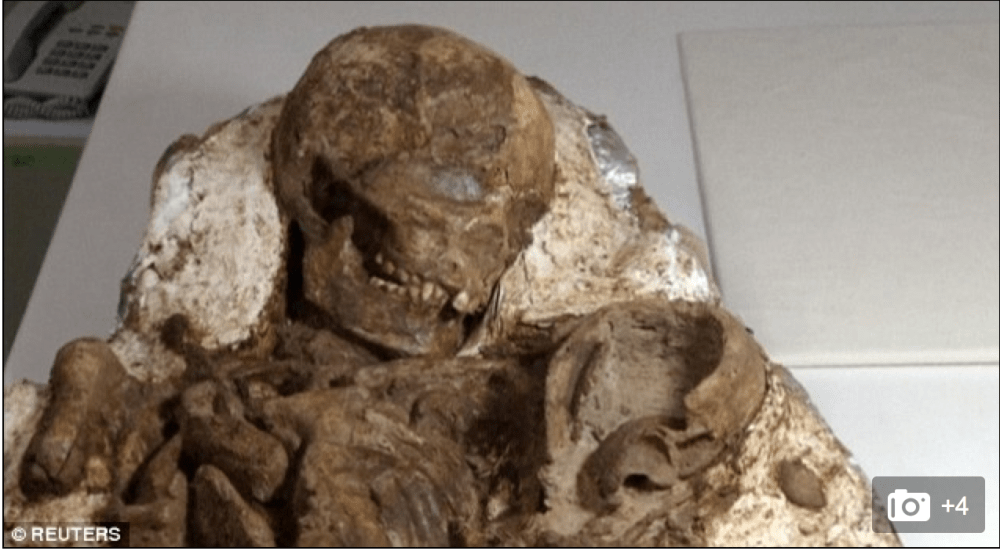

Archaeological child from the ‘Atele site in Tongatapu, Tonga (To-At 2/7) Figure 1: The 4800-year-old “mother and baby” found in Taiwan (source: Reuters)

Figure 1: The 4800-year-old “mother and baby” found in Taiwan (source: Reuters) Figure 2: Archaeologist cleaning the ‘mother-baby’ burial (photo: Reuters video).

Figure 2: Archaeologist cleaning the ‘mother-baby’ burial (photo: Reuters video).

Figure 2. Infant jar burials from the Iron Age site of Noen U-Loke, NE Thailand. Left: full-term infant, approximately 40 gestational weeks (burial 100); right: pre-term infant, or ‘fetus’, approximately 30 gestational weeks (burial 89). (Photograph courtesy of C.F.W. Higham)

Figure 2. Infant jar burials from the Iron Age site of Noen U-Loke, NE Thailand. Left: full-term infant, approximately 40 gestational weeks (burial 100); right: pre-term infant, or ‘fetus’, approximately 30 gestational weeks (burial 89). (Photograph courtesy of C.F.W. Higham)