There is an increasing number of online imaging resources and software useful for the bioarchaeology of infant and children. These resources are of particular use for teaching.

Online Imaging Resources and Software

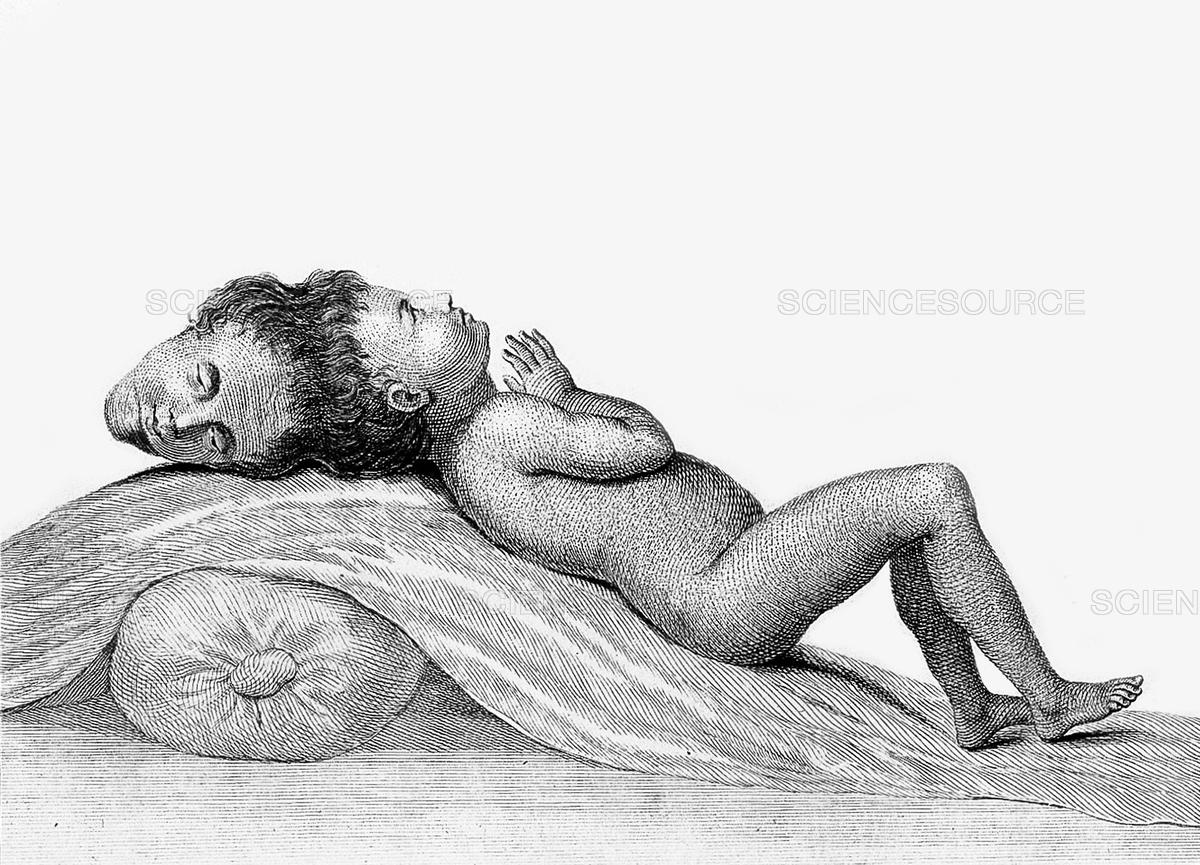

Gwen Robbins Schug from Appalachian State University (US) has developed Osteological Teaching Resources, which features a growing collection of 3D scans of human fetal and perinatal remains. Digitised Diseases, developed by the University of Bradford (UK), is a significant paleopathological resource with an impressive array of 3D models of bone pathology useful for comparative purposes. Infants and children are featured in many of their disease category types, particularly in the metabolic disease section. eSkeletons, an interactive resource for students in biological anthropology, contains limited child osteology resources. The AAOF Craniofacial Growth Legacy Collection, a database on

craniofacial development in modern children developed by the American Association of Orthodontists for clinical use, may be of use in teaching and research by bioarchaeologists. El Atlas de Osteología Infantil FACSO is being developed for teaching and learning purposes and includes infant reference material. Three-dimensional data sharing is starting to be used among paleoanthropologists for recording and sharing new fossil hominin finds, particularly because of their rare and unique nature.

However, it is our understanding that there are no open access 3D scan data of infant and child remains. There is also little software available featuring infant and child osteology. The interactive 3D skeleton viewer Dactyl (by Anthronomics), designed by Tim Thompson from the University of Teesside (UK), has some examples of child bones. Most bioarchaeologists construct their own databases for data collection in both lab and fieldwork situations. There is an increasing number of human fetal, infant, and child casts available for purchase from Bone Clones, Inc. and France Castings for teaching and research purposes.

• AAOF Craniofacial Growth Legacy Collection.

Extensive open-access database produced by the American Association of Orthodontists

Foundation (AAOF), which includes nine collections of longitudinal craniofacial growth and development records in the United States and Canada. Developed for clinicians, but also represents a useful resource for craniofacial development for teachers and researchers in the field of childhood bioarchaeology. Material includes skull, dental, and hand-wrist radiographs.

• Dactyl (by Anthronomics). Tim Thompson, University of Teesside, UK.

An interactive 3D viewer loaded with photo-realistic models of bones, allowing you to rotate and zoom in on each model. The viewer comes with three preloaded adult bone elements, and there are additional packs that you can purchase, which include a “non-adult pack” with 2 bones (femur and ilium). This app is available for purchase on iTunes and can be downloaded onto an iPad.

• Digitised Diseases. University of Bradford, UK.

An open-access resource featuring human bones that have been digitized, with a wide range of pathological-type specimens from archaeological and historical medical collections. Infant and child pathology cases including trauma, metabolic, and infectious disease. Includes photorealistic digital representations of 3D bones that can be viewed, downloaded, and manipulated on a computer, tablet, or smartphone.

• El Atlas de Osteología Infantil FACSO.

An open-access atlas project developed by students of physical anthropology at the University of Chile. This atlas is part of a larger project of developing human osteology resources for teaching and learning. The infant material is from the site of Pica 8, northern Chile, from the Late Intermediate Period.

• eSkeletons. University of Texas at Austin.

Useful interactive resource to learn about human skeletal anatomy and comparative primate skeletal anatomy. Limited child osteology, including a life-size print of juvenile human bones in their teaching resources. Useful for students of all stages.

eSkeletons. University of Texas at Austin.

• Robbins Schug, Gwen. Osteological Teaching Resources. Appalachian State University.

Provides 3D scans of human fetal bones to be used for teaching purposes. The database is added to over time, with the ultimate goal to provide scans of all the skeletal elements from fetuses of different ages and perinates, cases of pathology, and traumatic injury. For access email: Robbinsgm@gmail.com

A comprehensive online resource on childhood bioarchaeology published with Oxford Bibliographies is available here free to download.

This will be useful to all bioarchaeology and human osteoarchaeology students, and academics for research and teaching.

Halcrow, Siân E.; Ward, Stacey M. “Bioarchaeology of Childhood.” In Oxford Bibliographies in Childhood Studies. Ed. Heather Montgomery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Blogs

There are a very limited number of blogs on childhood from a bioarchaeological perspective, with this blog, obviously, dedicated to the topic. The Society for the Study of Childhood in the Past has a news blog as part of their WordPress website featuring member profiles, research and conference information, and other society-related news. Other popular bioarchaeological blogs, including Powered By Osteons and, regularly include material on childhood bioarchaeology. Katharina Rebay-Salisbury has also recently started a blog called Motherhood in Prehistory, focusing on her bioarchaeological work in western Europe, which includes information on fetuses and infants in the past.

• Halcrow, Siân, and Sally Crawford. Childhood in the Past News and Blog.

This blog, established in 2015, functions to keep the members of the Society for the Study of Childhood in the Past (cited under Associations) up-to-date with news on conferences,

meetings, new research, and other opportunities in the multidisciplinary field of childhood in the past.

• Killgrove, Kristina. Powered by Osteons.

Established in 2007, this popular blog showcases Kristina Killgrove’s own research and

teaching as well as stories on recent bioarchaeological research. These blog stories often

involve child bioarchaeology. Killgrove is also a contributor for Forbes and mental_floss.

• Rebay-Salisbury, Katharina. Motherhood in Prehistory.

Established in 2015, this blog shares stories related to the author’s work investigating

motherhood in prehistoric western Europe. Often her posts include information about infants and fetuses.

Video resource on age estimation of infants and children

https://childhoodbioarchaeology.org/2019/10/16/video-on-infant-and-child-age-estimation-in-bioarchaeology/

There are numerous other educational stories on childhood bioarchaeology that will be useful for students, e.g.

Why do we have baby teeth