The notorious ‘baby murderer’ from New Zealand

One of the most high profile cases of infanticide was committed by Minnie Dean in the late 19th century, also gaining infamy as the only woman in New Zealand to receive the death penalty for her crimes. During my childhood I heard many different stories of her hideous acts, made even more pertinent given that I grew up in the same small Southland town that these crimes were committed 100 years earlier. The stories revolved around how she murdered infants by piercing their fontanelles (‘soft-spots’ on the top of their heads) with hairpins, concealed them in hat boxes, and disposed of them in rivers. Kids in the playground at our local school used to taunt others by saying, “watch out or Minnie Dean will get you!”

Minnie Dean (1844-1895) was a ‘baby-farmer’ who cared for infants and children in an informal adoption relationship in exchange for money. This type of work was attractive to lower income women in New Zealand at the time, and in other parts of the British Empire. Those she took into care were largely illegitimate children.

Minnie and her husband Charles had financial issues, with records of filing for bankruptcy. After a fire destroyed their home they lived in a very small twenty-two foot by twelve foot house. At any one time there could be up to nine children under the age of three in her care.

In 1889 a six-month-old infant died in her care, and two years later a six-week-old baby died. The inquest from the six-week-old-baby concluded that the death was from natural causes and the other children at her house at the time were well cared for but that their living conditions were inadequate. In an era of high infant mortality (about 100 per 1000 births in NZ), it isn’t surprising that that some of the children would die from illness.

Minnie started to gain even more police interest when it was found that she had been looking for more children to care, as well as attempting, unsuccessfully, to take out life insurance policies on some of the babies.

In 1892 the police took into their care a three-week-old who Dean had adopted from a single mother for £25. The baby was reported to be in a malnourished state.

Then in 1895 Minnie was seen boarding a train carrying a young baby and a hatbox. However, on the return trip she was reported to only have the hatbox. She was subsequently arrested and police searched her property and found the bodies of two babies, later identified as Eva Hornsby and Dorothy Carter, and the skeleton of an older boy (whom Dean later claimed had drowned). An inquest found that Dorothy Carter had died from an overdose of opiate laudanum, commonly used to calm babies at the time.

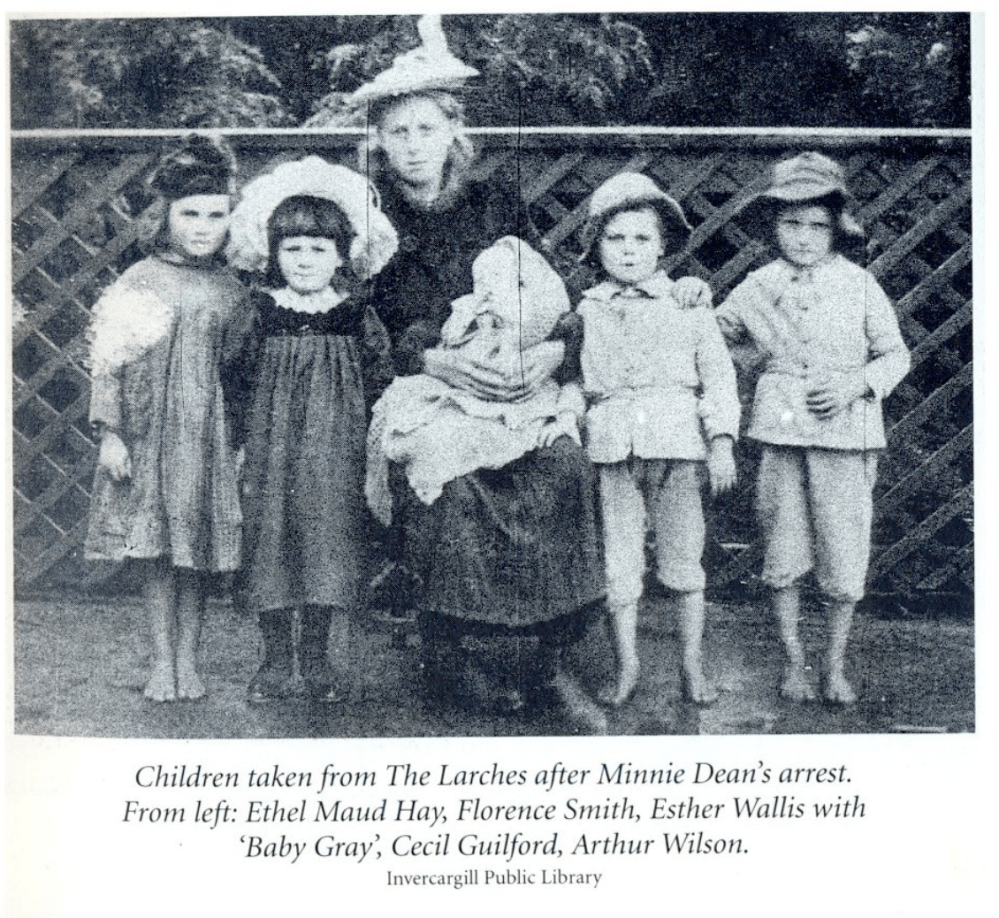

Before her death by hanging in August 1895, Dean wrote her own account of her life. In total, apart from her adopted children, she claimed to have cared for twenty-six children. Of these, five were found in good health after her arrest (figure below, and Esther Wallis, one of her adopted children), six had died in her care, and one had been given back to her parents. This leaves 14 children unaccounted for.

There was, understandably, intense public interest around Minnie Dean’s case. Around the time of her convictions macabre dolls in miniature hat boxes were said to have been sold as souvenirs outside the Invercargill courtroom where Dean was tried.

‘Minnie Dean dolls’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/minnie-dean-dolls, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 2-Oct-2014

‘Minnie Dean dolls’, URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/minnie-dean-dolls, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 2-Oct-2014

Later, Minnie Dean’s own defence lawyer Alfred Hanlon wrote:

Sober, home-loving folk from end to end of the country shuddered … when the grim and ghastly story of Minnie Dean’s infamy was narrated by the prosecution. Imagine a being with the name and appearance of a woman boldly using a public railway train for the destruction of her helpless victims, sitting serene and unperturbed in a carriage with one tiny corpse in a tin box at her feet and another enshrouded in a shawl and secured by travelling straps in the luggage rack at her head.

After her conviction the New Zealand government made the process of foster parenting more regulated to stop tragedies like this happening again.

In 1994 Historian Lynley Hood published a book, Minnie Dean: Her Life and Crimes, which raises some questions surrounding the fairness of her trial and the facts in the case. Was she a victim of hypocrisy of Victorian society doing the dirty work of caring for unwanted and illegitimate children? One will never truly know, but her name remains part of New Zealand history and grisly folklore today.

Figure 3: A newborn infant from Hambleden site (Credit: BBC)

Figure 3: A newborn infant from Hambleden site (Credit: BBC)